Epilepsy is a neurological disorder caused by abnormal and unpredictable electrical and chemical activity of neurons. During normal brain function, electrical and chemical information is passed from nerve cells in the brain to other parts of the body in a coordinated, orderly fashion. However, in patients with epilepsy, this pattern is interrupted by sudden and synchronized bursts of electrical energy, which, if intense enough, may briefly affect a person's consciousness, bodily movements or sensations. These physical changes are called epileptic seizures.

Some people with epilepsy have seizures only occasionally, while others have many every day. Epilepsy is estimated to affect 1 percent of the U.S. population – approximately 3 million people. Seizures usually occur without warning and without the person's awareness.

Drug therapy, brain surgery, vagus nerve stimulation and a ketogenic diet all are used to treat epilepsy, depending on the underlying cause. Of these treatment options, antiepileptic drugs, which prevent or reduce seizures, remain the cornerstone. Most epilepsy can be treated successfully with medications. Surgery is considered appropriate option when medication does not stop disabling seizures; another criteria is the patient’s type of epilepsy. A comprehensive evaluation by experts is required to make the recommendation for surgery. Our faculty providers at Seattle Children’s are experienced in surgical treatment in certain cases of epilepsy in children, visit their website to find out more.

Improved technology enables us to more accurately pinpoint where seizures originate in the brain, and other advances have made surgery safer. Surgery may involve removing brain areas that are causing seizures, or implanting a vagus nerve stimulator under the skin in the chest. The stimulator, a device about the size of a silver dollar, has wires that connect to, and stimulate, the vagus nerve in the left side of the neck.

Epilepsy is a condition in which a person has seizures. Seizures have many symptoms, depending on which brain areas are involved in the abnormal electrical activity.

-

Partial (focal) seizures involve a limited brain region, whereas generalized seizures begin on both sides of the brain.

-

Secondarily generalized seizures start in a limited brain areas, but then spread widely to both sides of the brain.

-

Simple partial seizures are focal seizures where the person remains full awake and aware during the seizure.

-

With a complex partial seizure, the person becomes unresponsive during it.

-

Generalized tonic clonic seizures (grand mal seizures) begin with stiffening of the whole body (tonic phase) followed by rhythmic shaking of the limbs and body.

-

Myoclonic seizures consist of sudden single jerks of the body, or part of it.

During absence seizures (petit mal seizures) the person has a brief loss of responsiveness, sometimes with repetitive eyelid flutter.

In more than half of all patients with epilepsy, no cause can be found. In the other group of patients, underlying causes can involve head injuries, brain tumors, genetic disorders, structural abnormalities in the brain and certain genetic, vascular and infectious illnesses.

Neurological evaluation: Diagnosing epilepsy relies heavily on a comprehensive patient health history and examination by a health-care provider. A description of the patient’s episodes is important – and since patients might be unaware of their seizure behaviors, a family member or witness should attend the initial exam.

EEG recording: An electroencephalograph (EEG) records brain waves through electrodes placed on the scalp to detect abnormal electrical activity in the brain. An outpatient EEG takes about two hours and can help diagnose epilepsy if it shows spikes or sharp waves –momentary electrical discharges that indicate irritability of the brain.

Video EEG monitoring: This test records brain waves and videotapes what happens during a patient’s seizures. Usually the patient is admitted to the hospital, and must wear 21 or more electrodes glued to the scalp. Antiepileptic medications may be reduced or halted to encourage seizures. This type of monitoring is performed to clarify a diagnosis when a patient’s seizures do not respond to treatment, and also to determine where seizures emerge to understand if a patient is a candidate for brain surgery.

Dense array EEG monitoring: The patient wears a head cap with 256 electrodes to record seizures. The high number of electrodes enable physicians to better identify the brain’s source of abnormal electrical signals. This technique is usually only used in patients being evaluated for brain surgery, when the standard video EEG monitoring study fails to adequately locate the seizures’ source.

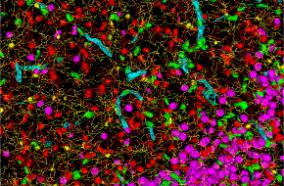

Invasive EEG monitoring: Sometimes EEG and scans cannot determine exactly where seizures arise. If a strong possibility exists that the patient is a candidate for epilepsy brain surgery, invasive monitoring is done. This involves surgically placing electrodes directly on the surface of the brain (subdural strip and grid electrodes) to record seizures. In certain situations, depth electrodes – small needle-like probes – are inserted to record from deeper brain regions.

Neuroimaging (scans): The most important test is the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to look for brain abnormalities that could cause epilepsy. Some tests are useful only for patients being evaluated for epilepsy surgery: Positron emission tomography (PET) scans reveal brain metabolism. Ictal SPECT studies measure blood flow in the brain. Functional MRI (fMRI) is used to find areas of the brain that support important functions such as movement, sensation, vision or language, and may be used to ensure that surgery won’t affect those areas of the brain. Computed tomography (CT) scans typically are less useful than MRI.

Neuropsychological testing: This assesses how a person’s epilepsy affects their memory, mental abilities and emotions. Sometimes patterns of results from this test can help to diagnose a patient’s condition or locate seizures’ origin in the brain.

Wada test: The Wada test is performed primarily on epilepsy surgical candidates to determine on which side of the brain speech and memory functions reside.

In a small number of cases, epilepsy is caused by a serious underlying condition such as a brain tumor, and complications stem from progression of the underlying problem.

In most cases, however, seizures cause epilepsy’s disabling effects: the inability to work or progress in school, the risk of injury or death, if seizures are not controlled. Patients with uncontrolled seizures that cause loss of responsiveness are at risk for vehicle accidents, and cannot safely or legally drive a vehicle. They are also at risk for drowning, falls, and other injuries. They should avoid heights and swimming or bathing without supervision. Rarely, prolonged, uncontrolled seizures can cause brain injury and death, in the absence of prompt intervention.

Very small risk (less than 1 percent per year) exists for sudden death in patients with uncontrolled epilepsy. This is called sudden unexpected death in epilepsy, and typically is unwitnessed. Physicians debate its cause.

The best way for most people with epilepsy to avoid such complications is to work closely with their health-care providers to control the seizures.