Richard G. Ellenbogen, MD, chair and professor of neurological surgery, takes living life by the golden rule one step further. He applies the platinum rule to everyone he meets: treat others the way they want to be treated.

For the past 25 years, that’s been the philosophy behind his work with neurological surgery residents at the University of Washington School of Medicine. It’s helped him connect with residents in more impactful ways, building what he refers to as his second family. In addition, the ideology bolstered his efforts to expand the residency program and make it more reflective of America. The more inclusive approach has also set the tone for how future neurological surgeons will provide needed care.

Reshaping neurosurgical education

Ellenbogen, a first-generation physician and surgeon, arrived at UW Medicine in 1997. He came to Seattle Children’s Hospital to focus on his passion — performing neurological surgery. At the time, he left behind roles as a chair and program director at Walter Reed Army Medical Center, the hospital where he began his medical career in 1983. And taking on another department leadership role wasn’t yet on his mind.

Within a year, however, his colleagues requested he take the helm. Once there, he recognized a significant need for clear direction in the neurological residency program. So, he took an unorthodox step. When he assumed the role of chair in pediatric neurosurgery in 1998, he also assumed responsibility for resident education.

“The students are like my second family, and I consider it incredibly important to mentor them correctly,” Ellenbogen says. “Mentoring is one of the most important things we do; it’s as important as scholarship, research and clinical care. It’s our way of paying it forward. If you want to change the world, you do it a person at a time.”

Thanks to his dedication, he was awarded a 2023 Parker J. Palmer Courage to Teach Award from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).

Throughout his tenure, the face and focus of the neurological surgery residency program have changed immensely. The result, Ellenbogen says, is a training program that more closely resembles America and is better able to meet the wide range of patient needs.

Under his leadership, the neurosurgery department has also developed a high-impact scholarship program rooted in two training grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). These awards ensure residents learn to write grants of their own, and they encourage underrepresented minorities to pursue careers in neuroscience. He says that with this extra training and guidance, 15 UW Medicine residents have earned chair or chief positions in their respective departments or divisions.

However, Ellenbogen hasn’t confined his efforts to UW Medicine’s neurological surgery residency program. Through multiple leadership roles, including serving as president of the Congress in Neurologic Surgeons and the American Society of Pediatric Neurosurgeons, as well as the chair of the American Board of Neurological Surgery, he has led a paradigm shift toward more inclusive, innovative education.

“We changed the way we treat military applicants, women and underrepresented minorities,” he explains. “You take your platform, and you go on the road. It’s not just a local mentoring and recruiting effort, but a national one. People begin to look at your program as an example, wondering how it became so diversified.”

Protecting brain health

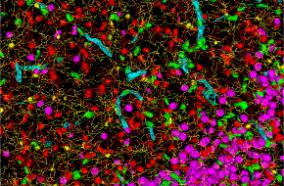

While preparing the next generation of neurological surgeons remains a top priority, Ellenbogen also dedicates time to exploring new neurological territory. Through his National Cancer Institute (NCI)-funded molecular imaging lab, he collaborates with the engineering department on campus to use immunofluorescent nanoparticles to highlight and target brain tumors. These particles detect antigens that trigger an immune response in the body and make them glow.

In addition, he leads a Paul Allen Brain Science Foundation project that concentrates on people who have experienced traumatic brain injury. His investigation maps their messenger RNA – the body’s molecules that carry genetic material needed to make proteins.

His interest in brain injury prompted Ellenbogen to accept a volunteer position as the co-director of the National Football League (NFL) Head, Neck and Spine Medical Committee. During his seven years in this role, from 2010 to 2017, he leveraged science and the heft of the NFL to advocate for greater concussion protection for young athletes. Not only did he advocate for sideline concussion diagnosis and new management protocols, but his efforts also secured $100 million in research funding and approved youth concussion laws in every state.

Setting UW neurosurgery apart

While the neurosurgery residency program is unique, other factors make the department different.

The program’s size — both by land mass served and patient volume — makes the department one of the most impactful in the country. UW Medicine Neurosurgery has the only neurosurgery program that serves the WWAMI region (Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, Idaho), an area that covers 27% of the United States. Physicians provide care across UW facilities which include the UW Medical Center – Montlake, Harborview Medical Center and the VA Puget Sound. Consequently, UW Medicine neurological surgeons have honed their expertise, performing roughly 6,000 to 8,000 procedures annually, Ellenbogen says.

Beyond having extensive surgical skills, UW Medicine faculty also showcase their innovative spirit in research. In the past five years, the department has published over 200 peer-reviewed papers, secured over 50 patents and launched six companies.

These accomplishments underscore the philosophy that has traditionally led the department and will continue to push it toward further growth.

“Our program is young, and we have an attitude committed to change,” Ellenbogen says. “I tell the faculty if we’re practicing the same way we were five years ago, we’re probably doing something wrong. We’re not afraid to try new methodologies and new techniques — we enjoy being on the cutting edge.”